Context

Tocqueville writes in a time where everyone had a philosophy of history. People believed that you can't understand politics without understanding the mechanisms of history.

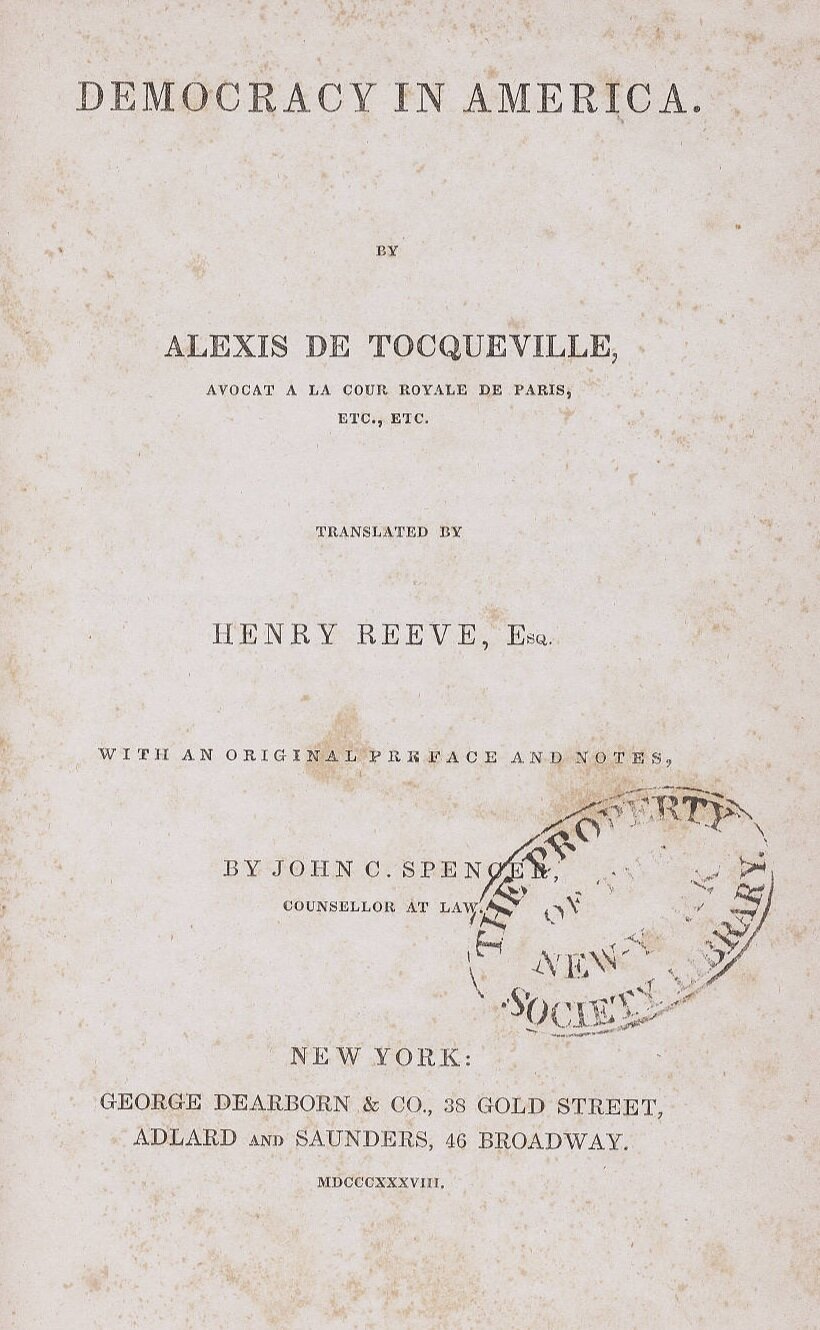

There are two general narratives of how political revolutions/progress occurs. The Aristotelian accounts is that any regime can dissolve into any other regime. The Platonic account is that there is a teleological progression (circular or linear) between different types of regimes. In this regard, Tocqueville is more of a Platonist. He believes in the inevitable progression of democracy.

Tocqueville's philosophy of history is heavily Christian. There was once a period of a rule of law. Effectively a caste system. Christianity brought down this caste system by enabling anyone to join in the ranks of the clergy. The clergy entered the government and started wielding power. Then lawyers and the bourgeoise slowly developed. The new middle class was spawned by Christian destruction of the old caste system and it was this new middle class that yearned for a new political system.

The leftist interpretation is that society is trending towards the good after this radical break happened. The right believe that society is declining. The right have three options: 1. withdraw from society 2. attempt to undo the revolution 3. begin a new revolution that brings old aspects back stronger than before (20th century Fascism).

Democracy in America is mostly addressed to the right. He doesn’t necessarily think that democracy is trending towards the absolute good but he does believe it is unstoppable. He wants the right to give up an illusion of the return.

Tyranny of the Majority

Tocqueville worried about three forms of tyranny of the majority: 1. institutional tyranny: that existing governmental systems could be used by the majority to abuse a minority. 2. future tyranny: that government could expand or dissolve into a tyranny. 3. psychological tyranny: that the majority could exercise a form of thought control that brought the best minds to a level of mediocrity.

In almost all of these scenarios, the tyranny that Tocqueville fears is mild but pervasive, a tyranny that claws away at your character and soul rather than one that harms your body.

Institutional Tyranny

Tocqueville thinks that because we elect officials, we feel much more confident in them wielding power so democratic officials get to wield more power than their aristocratic counterparts. And since every layer of government is, in some way, elected by the people -- this is the defining characteristic of American democracies -- the whole of society is simply this one homogenous mechanism of power.

Tocqueville worries about the potential for abuse, minorities simply have nowhere to hide in such a society where the people control the government in its entirety. (Not sure how much of his argument stands given the polarization of politics).

When a man or a party suffers from an injustice in the United States, to whom can he turn? To public opinion? That is what forms the majority. To the legislative body? That represents the majority and obeys it blindly. To the executive power? That is appointed by the majority and serves as its passive instrument. To the public police force? They are nothing but the majority under arms. To the jury? That is the majority invested with the right to pronounce judgments; the very judges in certain states are elected by the majority. So, however unfair or unreasonable the measure which damages you, you must submit.

Future Tyranny

There are various ways that government can increasingly take on more power such that its domain (and therefore what they majority can enforce and control) becomes total.

We could be jealous of priviledges so much so that we hand increasing power to the state to level our differences:

The loathing men feel for privilege increases as these privileges become rarer and less important, so that democratic passions would seem to burn the brighter in those very times when they have the least fuel. I have already accounted for this phenomenon. No inequality, however great, strikes the eye in a time of general social inequality, whereas the slightest disparity appears shocking amid universal uniformity; the more complete this uniformity, the more intolerable it looks. Therefore, it is natural that love of equality should thrive constantly with equality itself: to foster it is to see it grow. This ever-burning and endless loathing which democratic nations feel for the slightest privilege has an unusual effect upon the gradual concentration of every political right in the hands of a single representative of the state. Since the sovereign authority stands necessarily and indubitably above all the citizens, it does not arouse their envy and each citizen thinks that he is depriving all his fellow men of those powers that he grants to the crown. The man living in democratic ages is always extremely reluctant to obey his neighbor who is his equal; he refuses to acknowledge that the latter has any ability superior to his own; he distrusts his form of justice and looks enviously upon his power; he both fears and despises him; he likes to bring home to him the whole time that they are both equally dependent upon the same master. Any central power which pursues these natural feelings loves and promotes equality, for equality eases, extends, and guarantees the actions of such a power to an unusual degree.

Industry and its growth could demand much more infrastructure, both material and political, to be built. Government and industry is symbiotic, the more the latter expands the more the former becomes all-encompassing:

Industry normally causes a multitude of men to congregate in one place, establishing new and complex relationships between them. It exposes them to sudden and great alternations of plenty and poverty, during which public peace is threatened. Finally, this type of work can come to damage the health and even the lives of those who make money out of it or those who engage in it. Thus, the manufacturing classes have a greater need of regulation, supervision, and restraint than all other classes and it is to be expected that the functions of government will multiply as they do.

This is not a tyranny per se but Tocqueville worries that the industrial, capitalist class could get so powerful that they form an aristocracy.

Lastly, Tocqueville also warns of the possibility of a military leader not giving up his power and seizing the country by force.

Psychological Tyranny

I know of no country where there is generally less independence of thought and real freedom of debate than in America.

This section reconstructs Tocqueville’s analysis of Democratic thought policing in Democracy in America. In the 19th century, the French Aristocrat toured the United States and spent the next decade wrestling with a central question. How can a society which guarantees the most freedoms on paper be so limited in imagination, devoid of independent thinking, and conformist in reality? This conformity isn’t just a superficial problem either, but a subtle yet nonetheless deadly bondage that chips away at our character, distorts our thinking, and corrodes our very spirit – a bondage so forceful and pervasive that Tocqueville labelled it a “tyranny”.

Unlike modern commentators who may provide a timely diagnosis – blaming a particular political ideology or the recent polarization of politics – Tocqueville locates the source of bondage in the very democratic institutions and ideals that grant us freedom in the first place. His answer may be timeless, but we still need to keep the historical context in mind. When he comments on how unfree Americans were, he certainly did not have in mind as comparison the surveillance technologies of the 21st century nor the totalitarian regimes of the 20th. Tocqueville is contrasting the bondage of the democratic citizen to the freedom of European aristocrats who had considerable independence, even from the monarch. This may seem like a reason to dismiss his observations entirely. Aristocracies are part of the past; only a tiny population enjoyed this freedom; we shouldn’t dwell in a pessimistic critique of the freest regime we have today. But it is precisely this anachronism that makes his insights so unique and valuable. By contrasting democratic life to, perhaps, the most independent class in history, we can see how our freedoms are still limited in subtle ways. Under this light, it is we who are the pessimist and Tocqueville the optimist. For we look at democracies and say: “Yes, this is as free as man can be.” Tocqueville offers instead: “No, you can be much more!”

Tocqueville draws a sharp distinction between the influence of democratic institutions (e.g. elections) and democratic ideals (e.g. equality). Both will limit independent thinking but in different ways.

The defining characteristic of democratic institutions is the self-governance of the people. The political leadership is elected and, to a large extent, directed by the opinions of the masses. Ideas flow bottom-up, not top-down. A requirement of democratic citizenship is, therefore, to have an opinion on a wide-variety of topics. Ask any American, and they will gladly go on about anything from abortion, to economic policy, to global affairs. Ask almost any other nationality, and expect a puzzled look in response, wondering why you are asking them questions reserved for experts. From a young age, the American child is encouraged to form her own opinions, so much so that we expect beauty pageant contestants to have a ready-made foreign policy response to ISIS. The oddity of this social fact is perhaps visible only to the foreign eye: a fundamental perquisite of social life in America is to hold strong opinions on issues experts devote their entire lives to investigating. This social expectation is generated by the political demands of democratic institutions. If the people are to govern, the people must make up their own minds.

Doesn’t this encourage free-thinking? Common sense suggests that the expectation to be opinionated should produce a nation of inquisitive and liberated minds. Tocqueville does not deny that the American is more educated and informed than your average aristocratic citizen, most of whom are peasants. What is worrisome is the way we form and enforce our opinions on others.

Americans do not seek opinions from traditional forms of authority. There is a subconscious assumption that if we are equals, we must have equal access to the truth and the same capacities to reason. The democratic ideal of equality makes any authority figure appear inherently false and suspicious. Cautious of intellectual tyranny from above, Americans “search by oneself and in oneself alone for the reason of things.”

How this pans out in reality is a far cry from this Cartesian ideal. Most people are simply too busy to properly wrestle with all the different perspectives, much less the underlying assumptions. Even the philosopher, who spends every waking hour engaging with ideas, “believes a million things upon the authority of someone else.” Dogma – opinions accepted on nothing other than authority – is necessary simply because there are too many perspectives to be questioned and too many assumptions to be tested. When it comes to authorities of truth within a functioning society, the question to ask is not “if” but “where” and “how”. Tocqueville urges us not to take the American and his self-proclaimed independence at his word, and instead look for hidden springs of dogma.

The same ideal of equality that leads the American to distrust any traditional form of authority, makes him more trustful of public opinion. If we are all equals in our ability to reason, then truth shouldn’t lie with any singular person, no matter their credentials, but must instead rest with the greatest number of people, in public opinion. More so than any other regime, democracies look favorably upon the wisdom of the crowds. This is a marked difference from aristocracies where the authority of knowledge rested in the hands of a visible and select few. But just as the serf may adopt the ideas of the local priest, we too copy from authorities, even if they do not appear as such. We stitch together our beliefs from public opinion: a sound blurb on the late-night news, an echo from the community gathering, a post on social media. Because there is no explicit and visible authority to attribute our views to, we readily claim them as our own. We cling onto them ever the tighter, as fruits of our own intellectual labor, out of “pride as much as conviction.” When we say we are thinking for ourselves, too often that just means we forgot where we parroted it from.

More worryingly, the issues we are required to take a stance on are often heavily politicized. Certain stances – gun control, immigration policy, abortion laws, etc. – are mostly adopted on party lines. Asking about someone’s views on abortion is often less motivated by curiosity than a desire to place them on the spectrum, to label them as “friend” or “foe”. As a result, free thinking is even more threatened because it is often easier and more socially rewarding to pick the opinion that nets political advantages. If all my friends are liberal hippies, is it even an option for me to, upon careful research, conclude that climate change is blown out of proportion? Tocqueville’s insight is that the more external rewards there are around having the right opinion, the harder it is to be a free thinker and pursue truth for truth’s sake. When you liberate political power from a specific class, as democratic institutions do, you inject the political, and political rewards, across all of society. We shouldn’t be surprised that as more and more of our life – entertainment, sports, coronavirus, etc. – becomes increasingly partisan, it is harder and harder to have sober conversations about them.

Without a clear external authority dictating opinion, people feel a genuine ownership over their ideas. As a democratic citizen, I conceive of my opinions as “mine” and genuine, even if they come from external sources and are adopted for ulterior, political motives. The medieval courtier may secretly despise what he publicly accepts from an external authority. But the democratic citizen, believing himself to be the origin of his beliefs, endorses them wholeheartedly. Tocqueville praises this phenomenon and the character of responsibility it produces, but is nonetheless cautious of the side-effects. Because everyone in society has strong opinions, political allegiances and, thus, incentives to enforce these opinions, thought-control is much more pervasive than it ever could have been in aristocracies. Tocqueville’s claim is this: in aristocracies, there is a clear separation between the ruling class and the people, and even within the ruling class itself. Ideas don’t flow as freely and, therefore, society isn’t homogeneous. There’s always some safe harbor to explore outlandish ideas or, at least, enough people who don’t care enough to bother you. Even if the monarch wanted to control thinking, he can’t mobilize all of the people, all the time: “No monarch is so absolute that he can gather all the forces of society into his own hands and overcome resistance as can a majority endowed with the right of enacting laws and executing them.”

But, Tocqueville warns, when authority is bottom-up, when the people’s will determine the direction of the leaders, there is nowhere to hide. The ruling party share the opinions of the people because they were elected by them. And the people, now with a strong set of opinions and a deep sense of ownership over the political process, all become voluntary thought police, keeping each other inside the party line. Surveillance is carried out not through force or violence, but dirty glances, nasty remarks, and social ostracism. It is total and continuous. Tocqueville insists that when a democratic people makes its mind up on an issue, there is no room to explore alternatives. Anything outside the Overton window immediately becomes blasphemy.

But even when there isn’t a nation-wide consensus, policing on partisan lines can still smother independent thinking. It is the bottom-up nature that makes it so pervasive and effective. The homogeneous intellectual climate in our liberal universities is a good example. During class, in the dorms, at a party – students police each other non-stop in speech and action. They are not following orders from a central committee of political correctness, but simply participating in the democratic process which is inherently political. The result is an almost universal enforcement of the party line and an ideological homogeneity that could rival the achievements of the most effective central committees. As this example suggests, bottom-up policing is not only more pervasive but can also be more forceful because it coerces with a moral force. When the rare student deviates from the progressive ideal, he is not beaten or tortured, but made to feel like a worthless outcast. Tocqueville explains:

Under the absolute government of one man, despotism, in order to attack the spirit, crudely struck the body and the spirit escaped free of its blows, rising gloriously above it. But in democratic republics, tyranny does not behave in that manner; it leaves the body alone and goes straight to the spirit. No longer does the master say: “You will think as I do or you will die” he says: “You are free not to think like me, your life, property, everything will be untouched but from today you are a pariah among us. You will retain your civic privileges but they will be useless to you, for if you seek the votes of your fellow citizens, they will not grant you them and if you simply seek their esteem, they will pretend to refuse you that too. You will retain your place amongst men but you will lose the rights of mankind. When you approach your fellows, they will shun you like an impure creature; and those who believe in your innocence will be the very people to abandon you lest they be shunned in their turn. Go in peace; I grant you your life but it is a life worse than death.”

Tocqueville’s surprising insight is that the threat of violence used by an aristocratic monarch to control thought is often less forceful than the social forces within a democracy. The assumption here is that there is a moral force behind the people. If you rebel against an authority, you may gain the prestige of a martyr. But if you go against the people, you are an evil and worthless person. Tocqueville’s observation is that, with this moral force, bottom-up policing doesn’t even need to resort to physical punishment because it stamps out dissident ideas from the get-go: “The Inquisition was never able to stop the circulation in Spain of books hostile to the religion of the majority. The power of the majority in the United States has had greater success than that by removing even the thought of publishing such books.”

To be sure, it is not as if everyone in an aristocracy was a free-thinker. The social forces that restrict independent thinking exists in all societies. There will always be bottom-up policing. But it is inflamed by democratic institutions which require its citizens to have opinions around a wide range of issues and to form political allegiances around them.

The advantage of aristocracies, Tocqueville must think, is not in what they do have but in what they don’t have. People just don’t care about the wide range of issues that concern the democratic mind: they have no say in these matters and no parties hoping to win their votes. This is undesirable for a whole host of reasons. But, in so far as independent thinking is concerned, there is also no constant policing around these issues. Tocqueville concedes that aristocratic peoples are more ignorant – they hold less opinions. Democracies have, without a doubt, raised the averaged level of education. But aristocratic peoples are also less dogmatic – they hold less opinions out of ulterior, political motives. In such a society, someone who has the opportunity and urge to explore truth, granted a tiny minority, could do so without a pervasive social force policing their thought. Tocqueville is concerned that the social forces within American-style democracies will smother out the great, rare, and rebellious minds from the get-go and instead herd everyone into an above-average mediocrity.

If democratic institutions unleash social forces that limit our thinking through coercion, then the democratic ideal of equality furnishes our characters with similar habits, perspectives, and biases such that we naturally arrive at the same thoughts. Equality is the belief that we are fundamentally the same in essence. Any difference is either insignificant or the result of nurture. Democracies honor equality because they are meritocratic. In aristocracies, status is determined solely by birthright and remains stable for centuries on end. In democracies, no group of people is better in stock than another. Status is determined by merit. It is fluid and hierarchies are unstable. This is also the logic of the free market. Winners and losers change rapidly; your family lineage matters less than what and how much you can produce. Evidently, the ideal of equality is not exclusive to America nor democracies. We should not be surprised to discover the same effects on free thinking from equality in non-democratic regimes. Equality influences a society to the extent that it is meritocratic and allows for social mobility.

Equality shapes the democratic character to be pragmatic and oriented towards action. With equality comes meritocracy and with meritocracy comes opportunity. But this opportunity is a double-edged sword. Tocqueville observes that the aristocrat rarely worries about wealth and his status is more or less guaranteed. This frees the mind for more noble pursuits. Even the peasant is able to, in a much more limited sense, free his mind from worldly concerns, if not only for the reason that there is not much he can do to improve it. Our stations, as democratic citizens, aren’t fixed in life. We are given license to pursue material goods and improve our status. But this license is, at the same time, a bondage. Our gaze becomes directed only to the worldly and the mundane. Free to pursue status and wealth, the liberating “can” quickly becomes a demanding “ought”. Meritocracies, Tocqueville observes, envelope everyone in a state of agitation. Because our stations are not fixed, we always want more and fear losing what we already have. We are always engrossed in a state of action trying to improve and protect our lot. Under this light, the aristocrat and the peasant are mentally freed from worldly concerns, relatively to us, by being physically limited in their ability to change them. Even the rich do not enjoy the same leisure as the aristocrat did. The latter rests in the comfort that his status will never change, while the former must remain in a state of action to maintain his standing in society.

To be sure, our orientation towards constant action and our pursuit of worldly goods does not prohibit us from valuing ideas altogether. We quickly see the importance of intelligence for success and learn to appreciate it. But, as a result, we tend to value ideas only instrumentally for their usefulness. We are focused on utility, “aided much more by the opportunity of an idea … than its strict accuracy.” This pragmatism disposes us to value the useful and digestible ideas at the expense of the complex and profound. “In ages when almost every man is engaged in action, an excessive value is generally placed upon those rapid flights and superficial ideas of the intellect while its slower and deeper efforts are considerably undervalued.”

So, even though democracies may show a strong desire for knowledge, we must remember that “the desire to use knowledge is not the same as the desire to know.” Free-thinking, in Tocqueville’s opinion, requires a certain aristocratic leisure that is simply unavailable to the action-oriented man.” The mental habits which suit action do not always promote thought.” Tocqueville’s insight is that great ideas only come about when you pursue them for their own sake. They are never the result of a pragmatic calculus:

If Pascal had had in mind only some great source of profit or had been motivated only by self-glory, I cannot think he would have been able, as he was, to gather, as he did, all the powers of his intellect for a deeper discovery of the most hidden secrets of the Creator. When I observe him tearing his soul away, so to speak, from the concerns of life to devote it entirely to this research and severing prematurely the ties which bind his soul to his body, to die of old age before his fortieth year, I stand aghast and realize that no ordinary cause can produce such extraordinary efforts.

Equality furnishes the democratic mind with generalizations. The same pragmatism also leads the busy American to prefer generalizations that explain very much with very little. We are disposed to look for “common rules which apply to everything, to include a great number of objects in one category and to explain a collection of facts by one single reason” because our action-oriented life leaves little time for thinking. There is a further reason that we are inclined to generalizations, especially in matters regarding the human condition. The assumption of equality, that all humans are the same in essence, makes it natural to project observations of one individual onto the human whole. The same virtues and vices of one must apply to another. The best regime for one nation must also be the best universally. The moral standards of one epoch should judge all of history. We lose, if ever so subtly, this aristocratic instinct that different people are of different stock and should be evaluated according to different standards. The dangers of this tendency to generalize are obvious. We lose much nuance beneath our broad strokes. And our desire for a binary “good” or “bad” overlooks the complexity of the human experience.

Lastly, equality directs the democratic gaze towards progress. Aristocratic citizens can see the bounds on their potential, the scope of their occupation, and limits of their status more or less at birth. They acknowledge the potential for progress but in a much more limited way. The son of an ironsmith may think about how he can improve his craft, but he dare not dream of one day becoming the King. Democratic ambitions are not bound by any such restraints. The American child is told from an early age that: “You can be anything you want to be!” This encouragement is not entirely deceitful either. The child has a whole host of presidents, scientists, and CEOs with humble beginnings to look up to that lend credence to this promise. Coupled with the belief that we are of the same essence, one can only explain this wide variance in outcomes with the indefinite perfectibility of man. Democratic citizens believe in the boundless potential for the human subject to adapt and progress. Consequently, we live life constantly trying to be better and self-improve.

This disposition towards progress is not limited just to our lives but becomes a general perspective through which we view the world. Tocqueville offers an example: American ship makers build less durable vessels with the assumption that “the art of navigation is making such rapid progress that the best ship would soon outlive its usefulness if it extended its life more than a few years.” This belief in our indefinite perfectibility is a generator of a whole host of philosophical assumptions. Even the way we interpret time and history is linear rather than circular: as a continued progression of mankind itself.

It is hard to see how this perspective of progress can limit our thinking. It might be odd to even think of it as a perspective and not just plain fact in the first place. This only goes to show the degree which progress is embedded into our democratic psyche. Tocqueville warns us that we may be stretching the bounds of human perfectibility to excess and exaggerating what is possible. Can the child really be anyone he wants to? Furthermore, our lens of progress is, at the same time, an orientation towards the future. Tocqueville observes how the subject of a better future populates democratic poetry, as the subject of a glorious past did aristocratic poetry. We must be cautious not to devalue the past. If we think of ourselves as progressed, as better in every way, we overlook what can be learned from those who came before us.

A character oriented towards action, a mind fascinated with generalizations, and a gaze towards progress – these characteristics generated by the ideal of equality in turn generate numerous philosophical assumptions, predispose us to certain types of ideas, and makes us look for answers in similar places. But it is clear that as much as these tendencies frame and limit thought, they also lead the American to fruitful insights and innovative ideas. These weaknesses are, at the same time, strengths. Indeed, every political regime will carry within it assumptions that color its citizens perspectives. Tocqueville is highlighting ours so that we can become aware of them and their limitations.

It should be obvious by now that Tocqueville is neither an enemy of democracy nor America. On the contrary, he is a self-described “friend of democracy” and only came to America to study the most functional democracy in his time. Indeed, he is cautious of the potential for intellectual tyranny. But even this he concedes is somewhat necessary: no society can function without unity sustained by commonly shared opinions based on nothing but authority alone. Not everyone can or should be a free-thinker. Dogma is somewhat necessary for the healthy functioning of society.

Democracy in America highlights these sources of dogma that may not be obvious at first sight: hidden and decentralized but nonetheless restraining. Both democratic institutions and democratic ideals will always limit independent thinking, both to the benefit of societal cohesion as well as the detriment of independent thinking. This will not change as long as America remains a democracy. But Tocqueville does present the American with a genuine and meaningful choice: limit and contain these forces, and gain a degree of intellectual independence; neglect and inflame these forces, and expect an intellectual tyranny pervasive and restrictive beyond your wildest imagination. Just because the freedom of the intellect is granted on paper, does not mean it doesn’t have to be continuously fought for in reality.

Barriers against Tyranny

It is impossible to summarize all the possible barriers against tyranny. That is what the whole book is about: how to preserve freedom in an age of increasing equality. But there seems to be three key pillars.

First, the lawyer class is disposed to higher learning and order from the demands of their occupation. They can form a meritocratic aristocracy that controls democratic passions. Also the process of being a juror helps. It makes men feel like they are part of something larger, makes them respect the court's decisions and inhabits them in the mindset of judges.

Second, religion greatly curbs the tyrannizing force of the majority by giving men shared opinions, making them think in the long term, establish a code of morality, etc.

The last one is more local governments that institutionally prevent the majority from exercising too much power.

Freedom and Equality

Then, with no man different from his fellows, nobody will be able to wield tyrannical power; men will be completely free because they will be entirely equal; they will all be completely equal because they will be entirely free. Democratic nations aim for this ideal.

Tocqueville insists here that not only are freedom and equality not at odds with each other, as the common political intuition suggests, but that they are in harmony or even synonymous.

To unpack this unlikely synergy, we should first clarify what Tocqueville meant by both terms. By freedom, he refers not to the classical liberal notion of freedom (although it may be intimately connected) namely freedom from coercion. His freedom is an ability for self-governance. We get a hint of that in passages like these: “Under a free government … most public offices are elective.” The aristocrat who pursues all his hearts desires without coercion yet cannot assume political power is not free for Tocqueville. His freedom can be interpreted as an equality in wielding political power. Freedom becomes a subspecies of equality. It is no surprise then that “men may not become absolutely equal without being wholly free” for to be wholly equal in all conditions is to include being equal in possession of political power and thus free. Under this lens, free institutions are not institutions that protect people from coercion but rather ones that represent the authorship and will of the people.

By equality, Tocqueville meant an equality in all social conditions (and thus political conditions). The dangers of equality is that it encourages egoism and individualism in two ways. First, since everyone’s power is relatively equal, no one has the force to really effect a large amount of people, unlike the feudal lord. Since it is not even a possibility to effect those beyond one’s immediate circle, people’s interests and scopes narrow in onto their private spheres. Second, with the removal of a stable hierarchy, equality renders society in a constant state of flux. This unsettles the individual from any embedded social context.

The heightened degree of individualism makes democracies particularly susceptible to Tyranny. Free institutions prevent this, albeit not in the direct manner we intuitively think it would. Through the participation in free institutions, people learn about responsibility and get an education of the importance of society and the collective. Free institutions protect from tyranny not by directly preventing tyrannical coercion but by creating psychologically resilient individuals who form strong societal bonds. Again what is significant here is Tocqueville’s methodolical focus on the psychological. By focusing on the psychological he is able to connect the effects from various different spheres: religion, economics, politics, etc.

Herein lies the synergy between freedom and equality. Freedom limits the negative psychological impacts of equality: individualism and egoism. Of course, freedom can have its own faults that lead to anarchy. But in his discussion of the importance of political associations for civil associations, he makes it clear that it is through the exercise of larger freedoms do people get a better grasp of its stewardship: “Thus it is by enjoying a dangerous freedom that Americans learn the skill of reducing the risks of freedom.”

Individualism

We need to separate between four concepts. Individualism, egoism, sympathy and sacrifice.

Individualism is a disposition that only extend cares within a small circle. It is related to but not necessarily egoism which is to care only about oneself and treat everyone as a means to my ends. I may be an individual who only cares and works to better my family but nonetheless not be an egoist and respect the public good.

Individualism is a recently coined expression prompted by a new idea, for our forefathers knew only of egoism. Egoism is an ardent and excessive love of oneself which leads man to relate everything back to himself and to prefer himself above everything.

…

Individualism is a calm and considered feeling which persuades each citizen to cut himself off from his fellows and to withdraw into the circle of his family and friends in such a way that he thus creates a small group of his own and willingly abandons society at large to its own devices. Egoism springs from a blind instinct; individualism from wrongheaded thinking rather than from depraved feelings. It originates as much from defects of intelligence as from the mistakes of the heart.

…

Egoism blights the seeds of every virtue, individualism at first dries up only the source of public virtue. In the longer term it attacks and destroys all the others and will finally merge with egoism. Egoism is a perversity as old as the world and is scarcely peculiar to one form of society more than another. Individualism is democratic in origin and threatens to grow as conditions become equal.

Aristocrats were not individualistic. They cared a great deal about their lineage and country, their superiors and inferiors. Equality makes us individualistic in two ways. First, since everyone’s power is relatively equal, no one has the force to really effect a large amount of people, unlike the feudal lord. Since it is not even a possibility to effect those beyond one’s immediate circle, people’s interests and scopes narrow in onto their private spheres. This is why Tocqueville will say that the industrialist is worse to his workers than the feudal lord is to his serfs. Second, with the removal of a stable hierarchy, equality renders society in a constant state of flux. This unsettles the individual from any embedded social context.

In aristocracies:

Among aristocratic nations, families remain in the same situation for centuries and often in the same location. This turns all the generations into contemporaries, as it were. A man practically always knows his ancestors and has respect for them; he thinks he can already see his great-grandchildren and he loves them. He willingly assumes duties toward his ancestors and descendants, frequently sacrificing his personal pleasures for the sake of those beings who have gone before and who have yet to come. In addition, aristocratic institutions achieve the effect of binding each man closely to several of his fellow citizens. Since the class structure is distinct and static in an aristocratic nation, each class becomes a kind of homeland for the participant because it is more obvious and more cherished than the country at large. All the citizens of aristocratic societies have fixed positions one above another; consequently each man perceives above him someone whose protection is necessary to him and below him someone else whose cooperation he may claim. Men living in aristocratic times are, therefore, almost always closely bound to an external object and they are often inclined to forget about themselves. It is true that in these same periods the general concept of human fellowship is dimly felt and men seldom think of sacrificing themselves for mankind, whereas they often sacrifice themselves for certain other men.

And in democracies:

Among democratic nations, new families constantly emerge from oblivion, while others fall away; all remaining families shift with time. The thread of time is ever ruptured and the track of generations is blotted out. Those who have gone before are easily forgotten and those who follow are still completely unknown. Only those nearest to us are of any concern to us. As each class closes up to the others and merges with them, its members become indifferent to each other and treat each other as strangers. Aristocracy had created a long chain of citizens from the peasant to the king; democracy breaks down this chain and separates all the links.

Despite being more individualistic democratic man are also more sympathetic to the entirety of the human race. They are more willing to help with small deeds and relate as well as pity the suffering of others. This is because 1. they all consider each other equal and 2. there are more shared experiences for them to relate to each other.

But the democratic man is not disposed to making huge sacrifices like the aristocrat. To die for one's country is foreign to the democratic psyche.

In democratic ages, men scarcely ever sacrifice themselves for each other but they display a general compassion for all the members of the human race. One never sees them inciting pointless cruelty and when they are able to relieve another’s suffering without much trouble to themselves, they are glad to do so. They are not entirely altruistic but they are gentle.

The cynical reading of this is from Rousseau, who said that the wider the scope of sympathy the less possibility for action. The enlightenment philosopher loves mankind as to not love his neighbor.

Self Interest Properly Understood

As a result, Americans are never motivated by grand virtues and aesthetics but rather by utility and self-interest. Only things that concern their immediate sphere they find reason to pursue. Therefore, they need to reason if something benefits their self-interest before doing it. This gets to such an extreme point even when you ask the American who is genuinely helping another, he would explain it as just pursuing his own self-interest. Pragmatic character means that one can only be motivated by very immediate ends:

When the world was controlled by a small number of powerful and wealthy individuals, they enjoyed promoting a lofty ideal of man’s duties; they liked to advertise how glorious it is to forget oneself and how fitting it is to do good without self-interest just like God himself. At that time, such was the official moral doctrine. I doubt whether men were more virtuous in aristocratic times than in others, but they certainly referred constantly to the beauties of virtue; only secretly did they examine its usefulness. But as man’s imagination indulges more modest flights of fancy and everyone is more self-centered, moralists fight shy of this notion of self-sacrifice and dare not promote it for man’s consideration. They are, therefore, reduced to inquiring whether working for the happiness of all would be to the advantage of each citizen, and when they have discovered one of those points at which individual self-interest happens to coincide and merge with the interest of all, they eagerly highlight it. Gradually, similar views become more numerous. What was an isolated observation becomes a universal doctrine and in the end the belief is born that man helps himself by serving others and that doing good serves his own interest.

Discontent

Despite America's material prosperity, Tocqueville observed a deep-rooted sense of suffering. Here are some of his explanations why.

Physical Pleasures

Americans are more materialistic. This is because, unlike the aristocratic peasant, the american can actually work to improve his lot. The downside of this is that the peasant, values spiritual sphere more than the material sphere and is closer to God. American's focus on materialism rarely leads to true happiness:

At first, there is astonishment at the sight of this peculiar restlessness in so many happy men in the midst of abundance. Yet this is a sight as old as the world; what is new is to see a whole nation involved. The taste for physical pleasures must be acknowledged as the prime source of this secret anxiety in the behavior of Americans and of this unreliability which they exemplify every day.

Restlessness and Agitation

Meritocracy makes people restless and agitated. Because you "CAN" be more you feel like you "OUGHT" be more. In a way, we are both worse of than the aristocrat but also the peasant who is freed from being concerned with status.

When it is birth alone and not wealth which governs a man’s class, everyone knows precisely his place on the social ladder; he neither seeks to rise nor fears to fall. In a society so organized, men from the different castes have little contact with each other but, when chance contact does occur, they are ready to come together without wishing or dreading to lose their own position. Their relations are not based upon equality but they do not experience any restraint.

…

When an aristocracy based on money takes over from one based on birth, this ceases to be the case. The privileges of some people are still extensive but the potential for acquiring them is open to all. The result of that is that those who possess them are constantly obsessed by the fear of losing them, or of seeing them shared, and those as yet without them long to possess them at any cost or at least to appear to possess them if they fail, which is not impossible to achieve. Since the social importance of men is no longer fixed by blood in any obvious and permanent manner and since wealth produces innate variations, classes still exist but it is not easy to distinguish clearly their members at first glance…. Straightaway an unspoken war is declared between all citizens; some employ a thousand tricks to join, or to appear to join, those above them, while others constantly fight to repulse those who seek to usurp their rights, or rather the same person does both these things for, while he is attempting to infiltrate the level above him, he fights relentlessly against those working up from below.

Endless Ambition

Americans have endless ambition, an ambition that must be thwarted if not only for the fact that everyone else has its to. Because we are all equals and consider ourselves to have the same potential as others, we always want to be the best. But this unleashes a competitive force that inevitably upsets those ambitions:

When all the privileges of birth and wealth are destroyed, when all the professions are open to all, and when a man can climb to the top of any of them through his own merits, men’s ambitions think they see before them a great and open career and readily imagine they are summoned to no common destiny. Such, however, is a mistaken view which experience corrects daily. This very equality which allows each citizen to imagine unlimited hopes makes all of them weak as individuals. It restricts their strength on every side while offering freer scope to their longings. Not only are they powerless by themselves but at every step they encounter immense obstacles unnoticed at first sight. They have abolished the troublesome privileges of a few of their fellow men only to meet the competition of all. The barrier has changed shape rather than place. Once men are more or less equal and pursue the same path, it is very difficult for any one of them to move forward quickly in order to cleave his way through the uniform crowd milling around him. This permanent struggle between the instincts inspired by equality and the means it supplies to satisfy them harasses and wearies men’s minds.

Tocqueville Principle

The famous Tocqueville principle states that the more a society tends towards equality the more the inequalities look like great crimes. This is because they become muhc more apparent and unjust. So as society becomes more equal, people feel they are less equal and become more resentful (This is a different argument from GIrard).

One can imagine men enjoying a certain degree of freedom which wholly satisfies them. Then they savor their independence free from anxiety or excitement. But men will never establish an entirely satisfying equality. No matter what a nation does, it will never succeed in reaching perfectly equal conditions. If it did have the misfortune to achieve an absolute and complete leveling, there would still remain the inequalities of intelligence which come directly from God and will always elude the lawmakers. However democratic the state of society and the nation’s political constitution, you can guarantee that each citizen will always spot several oppressive points near to him and you may anticipate that he will direct his gaze doggedly in that direction. When inequality is the general law of society, the most blatant inequalities escape notice; when everything is virtually on a level, the slightest variations cause distress. That is why the desire for equality becomes more insatiable as equality extends to all. In democratic nations, men will attain a certain degree of equality with ease without being able to reach the one they crave. This retreats daily before them without moving out of their sight; even as it recedes, it draws them after it. They never cease believing that they are about to grasp it, while it never ceases to elude their grasp. They see it from close enough quarters to know its charms without getting near enough to enjoy them and they die before fully relishing its delights. Those are the reasons for that unusual melancholy often experienced by the inhabitants of democratic countries in the midst of plenty and for that distaste for life they feel seizes them even as they live an easy and peaceful existence.

Growth as a Requirement for Democracy

Democracies generate a lot of discontent, envy, and resentment. If they aren't channeled into productive, positive-sum ends, they are channeled into bitter party disputes. The best gift to America was its wide frontier that gave everyone a way to satisfy their ambition without stealing from their neighbor. The same could be said about economic growth. Perhaps it too is a necessity for democratic functioning.

In the lucky circumstances which have supported and confirmed the establishment and continuance of the democratic republic in the United States, the most important is the choice of the country itself which Americans inhabit. Their fathers have given them the love of equality and freedom but it was God himself who granted them the means of long remaining equal and free by his gift of this boundless continent.

General prosperity supports the stability of all governments, but especially democratic governments which depend upon the attitudes of the greatest number and primarily upon the attitudes of those most exposed to privations. When the people rule, it is vital that they are happy, to avoid any threat to the stability of the state. Wretchedness has the same effect upon them as ambition does upon kings. Now, those physical causes, unconnected with laws, which can lead to prosperity are more numerous in America than in any other country at any time in history.

…

The territory of the Union provides limitless scope to human activity: it offers inexhaustible supplies for industry and labor. The love of wealth, therefore, replaces ambition and prosperity quenches the fires of party disputes.

Industry and Democracy

Wealth over Politics

Tocqueville believes that the top talent in democracies go and pursue wealth because political power is unstable and there is no real independence (you are dictated by the will of the people). They also don't get the respect they do in public life as they do in private life and so don't bother trying.

In fact the wealthy in America, in public life, have to appear to be poor, to have friends in low places. There is a deep insecurity and disdain for democratic processes by the rich, because of how powerful the people are:

Just look at this opulent citizen. Wouldn’t you say he is like a medieval Jew who dreads that his wealth might be discovered? His clothes are simple and his demeanor is modest. Within the four walls of his house he adores luxury; he allows only a few chosen guests, whom he insolently calls his equals, to penetrate this sanctuary. No European aristocrat shows himself more exclusive in his pleasures, more jealous of the slightest advantages of his privileged position than he is. Yet here he emerges from home to make his way to work in a dusty den in the center of a busy town where everyone is free to accost him. On his way, his shoemaker might pass by and they stop; both then begin to chat. What can they say? These two citizens are concerned with affairs of state and will not part without shaking hands. But beneath this conventional enthusiasm and amid this ingratiating ritual toward the dominant power, you can easily perceive in the wealthy a deep distaste for the democratic institutions of their country. The people are a power they both fear and despise.

On the Industrialist Aristocracy

The most likely way that aristocracies will reappear in democracies is through wealth and industry. Tocqueville reasons that with the division of labor, you are going to get a class of smarter and smarter class of managers that needs to deal with more and more complex problems. But you are also going to get a less and less educated working class that focuses more and more on specificities.

A naïve reader, given Tocqueville's praise for aristocracy, may take this to be a positive thing to be celebrated. But this aristocracy, Tocqueville believes will have all the negatives of the old one and none of the positives.

First, this class will not be stable enough to form a class consciousness and leisurely character that was so generative of creative insights. Because of the competitive nature of democracies and the inherit instability within them, they need to be disposed to action as well. Capitalist aristocracies do not escape the same psychological problems that plague the democratic masses. Take the urge for work and pragmatism: while aristocrats of old saw it as repugnant, and leisure as virtue, today’s elites are more enslaved by work than many of their employees! Furthermore, the capitalistic elite does not seem to have its own cultural values. In aristocracies, culture flows top-down. In democracies, culture flows bottom-up, it seems like what, in no small part, determines the cultural values of the capitalist-aristocracy starts from the masses: Hollywood, memes, pop music, major sports. Lastly, instead of nobility in character and pride, it is my observation that the richer the household the child is born in, and the more they hold equality as an ideal, the more it produces a sense of guilt. Since the default position is equality, their wealth does not bring forth a reason for pride or a legacy to maintain and standard to uphold but a sentiment comparable to survivors guilt.

Second, they are worse to their workers than the lords were to their serfs. This is because, Tocqueville thinks, by conceiving of themselves as so much better and power, and having a historical relationship, the old aristocracy felt a degree of responsibility to the people below them that isn't the case anymore in societies where people are equal:

Not only are the rich not firmly united to each other, but you can also say that no true link exists between rich and poor. They are not forever fixed, one close to the other; moment by moment, self-interest pulls them together, only to separate them later. The worker depends upon the employer in general but not on any particular employer. These two men see each other at the factory but do not know each other anywhere else; and while they have one point of contact, in all other respects they keep their distance. The industrialist only asks the worker for his labor and the latter only expects his wages. The one is not committed to protect, nor the other to defend; they are not linked in any permanent way, either by habit or duty. This business aristocracy seldom lives among the industrial population it manages; it aims not to rule them but to use them. An aristocracy so constituted cannot have a great hold over its employees and, even if it succeeded in grabbing them for a moment, they escape soon enough. It does not know what it wants and cannot act. The landed aristocracy of past centuries was obliged by law, or believed itself obliged by custom, to help its servants and to relieve their distress. However, this present industrial aristocracy, having impoverished and brutalized the men it exploits, leaves public charity to feed them in times of crisis. This is a natural consequence of what has been said before. Between the worker and employer, there are many points of contact but no real relationship. Generally speaking, I think that the industrial aristocracy which we see rising before our eyes is one of the most harsh ever to appear on the earth; but at the same time, it is one of the most restrained and least dangerous.

War

The democratic people do not want revolutions or wars. This is because of the asset owning middle class. It is clear what people will lose if they fail but it is not clear what is to be won if they win. Democratic armies want war more than aristocratic armies because it is the only way for them to win status.

Democratic armies will be worse prepared than aristocratic armies at the beginning of the war because the democratic mores of pragmatism, material comforts is in conflict with the heroism and honor virtues present in the military. As a result, the best people do not go into militaries.

He does present a very hopeful idea towards the democratic chain of command, however:

When the officer is a nobleman and the soldier a serf, the one rich and the other poor, the one educated and strong, the other ignorant and weak, the tightest bond of obedience can easily be established between these two men. The soldier is broken in to military discipline, even, so to speak, before entering the army, or rather, military discipline is merely the completion of social enslavement. In aristocratic armies, soldiers quite easily become virtually insensitive to everything except the orders of their leaders. They act without thought, they triumph without passion, and die without complaint. In this condition, they are no longer men but still very fearsome animals trained for war.

…

Democratic nations are bound to despair of ever obtaining such blind, detailed, resigned, and unvarying obedience from their soldiers as aristocratic nations can impose upon them with no effort at all. The state of society does not prepare men for this and they would run the risk of losing their natural advantages by wishing artificially to acquire it. In democracies, military discipline should not attempt to obliterate men’s creative freedom; it can only hope to control it so that the resulting obedience, though less ordered, is more eager and more intelligent. It is rooted in the very will of the man who obeys it; it relies not only upon instinct but also upon reason and, consequently, will automatically grow stricter as danger makes this necessary. The discipline of an aristocratic army is apt to relax in wartime because it is founded upon habit which is upset by war. But the discipline of a democratic army is strengthened in the face of the enemy because soldiers see very clearly the need to be silent and to obey to achieve victory.

Mores and Family

Tocqueville presents a quite idealistic picture of democratic family life. His essential point, commenting on parenting and sibling relationships, is that without rigid hierarchies, the artificial is taken away and the natural emerges and shines all the more brightly because of it within these relationships:

But such is not the case with the feelings natural to man. The law seldom avoids weakening such feelings by striving to mold them in a certain way and by wishing to add some thing, it almost always removes some thing from them, for they are always stronger when left alone.

…

I do not know whether, all in all, society stands to lose by this change but I am inclined to think that individuals gain from it. I think that as customs and laws are more democratic, the relations of father and sons become more intimate and kinder. Rules and authority are less in evidence; trust and affection are often greater; it seems as though natural ties draw closer while social ties loosen.

…

I think that it is not impossible to encapsulate in a single sentence the main sense of this chapter and several others preceding it. Democracy loosens social ties but tightens natural ones; it draws families more closely together while separating citizens.

In an aristocratic society, familial order is given on authority "because I said so". In democracies, parents treat their kids as if they were equals.

As far as the romantic relationship goes, he believes that womanly virtues are raised to being equal with masculine ones but women are not being forced to be men. American women are much more independent but lose a degree of warmness to them:

I realize that such a method of education is not free from danger; I am fully aware as well that it will tend to develop judgement at the cost of imagination and to turn women into virtuous and cold companions to men, rather than tender and loving wives. Although society is more peaceful and better ordered as a consequence, private life has often fewer charms. But those are minor ills which must be braved for a greater good. At the point we have now reached, we no longer have a choice: we need a democratic education to safeguard women from the dangers with which democratic institutions and customs surround them.

Interconnectedness of Politics, Religion, and Industry

If there is one thing to take away from this book it is how truly interconnected every aspect of a society is. Politics, religion, and industry these activities and the rules that govern them all shape our psyche in one way or another. It is through their psychological effects that these seemingly separate domains are so dependent on each other.

How Industry Supports Politics

Take inheritance laws for example. Seems like its not a big deal. But depending on whether the eldest son inherits everything or every kid inherits an equal share, an aristocracy gets created or destroyed:

When framed in a certain way, this law unites, draws together, and gathers property and, soon, real power into the hands of an individual. It causes the aristocracy, so to speak, to spring out of the ground. If directed, however, by opposite principles and launched along other paths, its effect is even more rapid; it divides, shares out, and disperses both property and power.

But the division of property doesn't only limit a material aristocracy. It also forms a psychological character that is not too concerned with family lineage and more concerned about the present:

But the law of equal division exercises its influence not merely upon property itself, it also affects the minds of the owners, calling their emotions into play. Huge fortunes and above all huge estates are destroyed rapidly by the indirect effects of this law.

…

Among nations where the law of inheritance is based upon the rights of the eldest child, landed estates mostly pass from generation to generation without division. The result is that family feeling takes its strength from the land. The family represents the land, the land the family, perpetuating its name, history, glory, power, and virtues. It stands as an imperishable witness to the past, a priceless guarantee of its future.

…

When the law of inheritance institutes equal division, it destroys the close relationship between family feeling and the preservation of the land which ceases to represent the family. For the land must gradually diminish and ends up by disappearing entirely since it cannot avoid being parceled up after one or two generations.

…

This so-called family feeling is often based upon an illusion of selfishness when a man seeks to perpetuate and immortalize himself as it were in his great-grandchildren. Where family feeling ends, self-centeredness directs a man’s true inclinations. As the family becomes a vague, featureless, doubtful mental concept, each man focusses on the convenience of the present moment and, to the exclusion of all else besides, thinks only of the prosperity of the succeeding generation and no more. He does not aim to perpetuate his family or, at least, seeks to perpetuate it by other means than that of a landed estate.

How Politics Support Industry

In like manner, democratic institutions which force people into congregating and expressing their will through association also teach men laws of association necessary for industrial endeavors:

In civil life, every man can, if needs be, fancy that he is self-sufficient. In politics, he can imagine no such thing. So when a nation has a public life, the idea of associations and the desire to form them are daily in the forefront of all citizens’ minds; whatever natural distaste men may have for working in partnership, they will always be ready to do so in the interests of the party. Thus politics promotes the love and practice of association at a general level; it introduces the desire to unite and teaches the skill to do so to a crowd of men who would always have lived in isolation. Politics engenders associations which are not only numerous but spread very wide.

How Religion Supports Politics

Religion also provides deep moral intuitions that are indispensable for politics. He attributes the initial democratic urge, at least in New England, to the puritan desire to build a society where people can worship God without hinderance. In a Weberian move, contra-Marx, Tocqueville finds the essence of democratic thinking in Christianity:

In my opinion, it would be wrong to see the Catholic religion as a natural opponent of democracy. Among the different Christian doctrines, Catholicism seems to me, on the contrary, to be one of the most supportive of the equality of social conditions. For Catholics, religious society is composed of two elements: the priest and the laity. The priest rises alone above the faithful: beneath him all are equal.

The Tensions of Religion and Politics

But dependencies are not always symbiotic. Tocqueville warns religious leaders from ever getting engaged with politics in fears that the fleeting nature of politics and political parties will bring down the timeless trust in religion:

Mohammed drew down from heaven into the writings of the Koran not only religious teachings but political thoughts, civil and criminal laws and scientific theories. The Gospel, in contrast, refers only to general links of man to God and man to man. Beyond that, it teaches nothing and imposes no belief in anything. That fact alone, leaving aside a thousand other reasons, suffices to show that the first of these two religions could not possibly prevail for long in times of enlightenment and democracy, while the second is destined to have dominance in these times as much as in any other.

…

If I pursue this same investigation further, I discover that to enable religions, humanly speaking, to thrive in democratic periods, not only must they carefully remain within a circle of religious matters but also their power depends even more upon the nature of their beliefs, their external structures, and the duties they impose.

The Inevitability of Equality

The gradual unfurling of equality in social conditions is, therefore, a providential fact which reflects its principal characteristics; it is universal, it is lasting and it constantly eludes human interference; its development is served equally by every event and every human being.

Tocqueville, in the introduction to his book, explains one of the core reasons for the writing of On Democracy in America: the inevitable democratic destiny of Europe. While this destiny is guaranteed, for the reasons I will soon discuss, its successful implementation is not so, a fact that was blatantly obvious in, say, the French Revolution. Investigating why Tocqueville believes the march of democracy and its egalitarian ideals is inevitable is not only critical to understanding the motives behind his work but will also be informative in analyzing the trajectory of the modern world, a world in which democratic regimes are showing increasing signs of strain.

The rise of democracy coincided with one of the defining characteristics of modernity: capitalism. Capital revealed the stubborn class distinctions that were so entrenched in society to be a hinderance on commerce: before the eyes of a trader, everyone is equal in so far as they can pay. The great equalizer of the free market began eroding previous class distinctions in favor of the more egalitarian meritocratic system: “The influence of money began to assert itself in state affairs. Business opened a new pathway to power and the financier became a political influence both despised and flattered.”

While this trend may have been operating in the background, the inflection point happened, so Tocqueville suggests, at two key junctures. The first juncture is the introduction of private property as opposed to owning property within Feudal tenure. This is, for Tocqueville, an inflection point because it seems that the very introduction of private property set up a system in place that began eroding concentrated power of the wealthy that gradually lead to egalitarianism:

As soon as citizens began to own land on any other than a feudal tenure and when emergence of personal property could in its turn confer influence and power, all further discoveries in the arts and any improvement introduced into trade and industry could not fail to instigate just as many new features of equality among men. From that moment, every newly invented procedure, every newly found need, every desire craving fulfillment were steps to the leveling of all. The taste for luxury, the love of warfare, the power of fashion, the most superficial and the deepest passions of the human heart seemed to work together to impoverish the wealthy and to enrich the poor.

This, in our era when the examination of political economy has been so influenced by Marx and neo-Marxian thinking, is a deeply interesting and surprising claim. The introduction of private property, contra Marx, isn’t responsible for wealth concentration but rather wealth dissemination. (I guess Marx would agree that capitalism is more equal than feudalism) Unfortunately, Tocqueville does not give further elaboration as to why every improvement to industry and the economy post-property is an equalizing force. A first, and frankly quite uninteresting resolution, would be that it equalizes the old strongholds of power within Feudalism. While this could be included into what Tocqueville was hinting at, I doubt this explanation covers the entirety of his claim.

The second inflection point, one whose exact emergence is much harder to pinpoint than the first, is when we began to control nature with rationality:

From the moment when the exercise of intelligence had become a source of strength and wealth, each step in the development of science, each new area of knowledge, each fresh idea had to be viewed as a seed of power placed within people’s grasp. Poetry, eloquence, memory, the beauty of wit, the fires of imagination, the depth of thought, all these gifts which heaven shares out by chance turned to the advantage of democracy and, even when they belonged to the enemies of democracy, they still promoted its cause by highlighting the natural grandeur of man.

His idea seems to be that every act of human achievement over the natural world or manifestation of cultural brilliance has also contributed to the development of democracy. This may also be quite a surprising claim for the modern academic that has associated the control of nature with the oppressive and non-democratic control of society by a minority. What is most surprising is his final sentence within this arch: that even those who use these advancements of control against democracy, accelerate the emergence of democracy by displaying the goodness and power of humanity at large. What’s implicit in his argument is that should one believe in the grandeur of man then a democratic society, a mode of organization which gives the most freedom for this grandeur to naturally develop, would also be preferred.

Tocqueville further broadens the scope of this already surprising claim. Every action in history, whether for or against democracy explicitly, has engendered it in some way:

Everywhere we look, the various events of people’s lives have turned to the advantage of democracy; all men have helped its progress with their efforts, both those who aimed to further its success and those who never dreamed of supporting it, both those who fought on its behalf and those who were its declared opponents; everyone has been driven willy-nilly along the same road and everyone has joined the common cause, some despite themselves, others unwittingly, like blind instruments in the hands of God.

A Real Choice

Despite this necessity, Tocqueville is not a fatalist. We are presented with genuine choices within this inevitability.

It's not so much democracy that I believe Tocqueville argues is marching on at a steady pace but rather the ideal of equality. This is a metaphor he uses to describe this unrelenting march:

The Christian nations of our day appear to me to present a frightening spectacle; the change carrying them along is already powerful enough for it to be impossible to stop yet not swift enough for us to despair of bringing it under control. Their destiny is in their own hands but it will soon slip from their grasp.

It's really important to pay attention to metaphors in philosophy. If truth is buried, we need tools, if truth is veiled, we need to remove something. If truth is a journey, we need a map. Depending on the metaphor, we are given different suggestions. But of course, sometimes stories/metaphors are just not vibrant enough to capture the intended meaning. The message he wants to send with this metaphor is, like a boat on a river, we are all heading towards the direction of equality whether we like it or not. But there is a genuine control of the outcome, whether its positive or negative.

What he is worried about is that equality in conditions will result in the tyranny of the majority in many different ways. The tools we can protect freedom must be natural to/conducive to equality itself. Ie. We can't ever go against the value of equality, we have to work with it because it is the dominant culture force of the time.

On the other hand, I am convinced that all those who will be alive in the coming centuries and might try to base their authority on privilege and aristocracy will fail. All those who might wish to attract and retain authority within one single class will also fail. At the present time there is no ruler so skillful or so strong that he could establish despotism by restoring permanent distinctions of rank between his subjects; nor is there a legislator so wise or so powerful that he is capable of maintaining free institutions without adopting equality as his rst principle and emblem. Thus, all those who now wish to found or guarantee the independence and dignity of their fellows should show themselves friends of equality, and the only worthy means of appearing such is to be so: upon this depends the success of their sacred enterprise.

…

Hence it is not a matter of reconstructing an aristocratic society but of drawing freedom from within the democracy in which God has placed us.

Responsibility and Liberty

Tocqueville articulates a reciprocal, dependent relationship between a healthy form of patriotism – which I take to be an individually rooted and initiated responsibility for the collective – and liberal political structures.

First, liberal political structures depend upon a culture of responsibility. Said political structures, as outlined by Tocqueville, could be categorized by high governmental centralization and low administrative centralization. That is to say, matters of national concern such as diplomacy are managed by a centralized authority while more specific issues such as education and the judiciary were managed by localized governments. As a result, the healthy functioning of the system required individuals who took upon more responsibility onto their own shoulders when compared to their European counterparts: “In America, not only do institutions belong to the community but also they are kept alive and supported by a community spirit.” Political freedom at the highest level requires constant restraint from institutions at the lowest level that are efficient, responsible, and careful at guarding their own interests. It has become more evident why Tocqueville was so suspicious of Democracy being enforced upon a people without the prerequisite cultural software.

Second and more insightful, liberal political structures cultivate a cultural of responsibility. Put in another way, genuine responsibility and, when that responsibility is projected on the collective, patriotism depends on liberal political structures.

Patriotism does not long prevail in a conquered nation. The inhabitant of New England is devoted to his township, not because he was born there as much as because he views the township as a strong, free social body of which he is part and which merits the care he devotes to its management.

Tocqueville seems to suggest that the very fact a citizen recognizes that the government is not made of an antagonistic body of individuals whose interests are in irreconcilable conflict with their own and instead by people who represent his interests is the dominating force that inspires them to tend to the government. In short, it is the recognition that the government is not an “other” but part of “me” which generates this attitude of responsibility. It is evident why localized government is so central then: the closer the governmental body is to me, the easier it is to identify with it.

These localized governments are also advantageous because those who pursue political power are more likely to do it out of affection than ambition: “the New England township is so constituted as to give a place to the warmest affections without arousing the ambitious passions of the human heart.” And the constituents are more willing to forgive whatever mistakes that are eventually made: “If the government makes mistakes, and it is easy enough to point them out, they are hardly noticed because the government emanates from those it governs and, as long as it acts as well as can be expected, it is protected by a sort of paternal pride.”

At the end of the day, it is not efficiency or how local governments are better suited to meet the needs of their constituents that Tocqueville appeals to; in fact, he agrees that a nation would be more efficient the more centralized it becomes, at least in the near future. But it is the ability for decentralized governing structures to create a sense of patriotic responsibility, which is more important than any other factor for the flourishing of a society, that is its prime virtue: