This discourse addresses one of the "grand and finest" questions ever raised. Because it is not concerned with metaphysical subtleties but truths that affect the happiness of mankind.

Rousseau expects universal blame for taking this negative position. He has sided with a few wise men against the fashionable intellectuals who style themselves "freethinkers" AND the public.

What's noteworthy is how he describes siding with someone as having been honored by them. The idea isn't to escape the desire for recognition but to delight in recognition from the right sources.

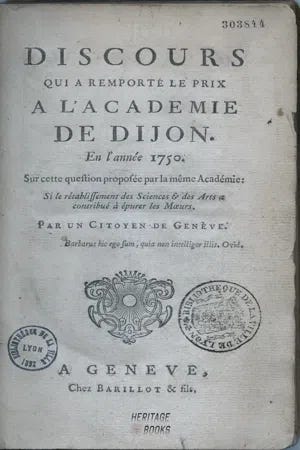

He mentioned that he restored the Discourse which it was awarded the prize with few slight changes.

Rousseau reframes the question by adding the suggestion that enlightenment may have contributed to corruption: "Has the restoration of the Sciences and Arts contributed to the purification of Morals, or to their corruption?"

Rousseau introduces himself as someone who "knows nothing" and is not unproud of it. This is the Socratic ignorance of the wise.

Rousseau understands the difficulty of the task in front of him to argue against science in front of a celebrated academy. The way he is going to argue against this more is to appeal to an even more important/deeply held more: virtue.

He is buttering up people listening to his speech. It is evident that he thinks they are neither erudite nor virtuous but he says here they are both.

Rousseau says by defending truth there is a Prize that cannot escape from him: the prize he will win from the depth of his heart.

Rousseau calls the progress in knowledge of the past few generations "a grand and a fine spectacle." The progress of knowledge combines a going out to the stars and a return to oneself. Studying of the world but also, more importantly, study of man.

He starts his history in the middle ages which is "state worse than ignorance" because it believes because it can regurgitate the big words of Aristotle it has knowledge. False knowing.

What ended the middle ages was the fall of the throne of Constantine that brought back Greek antiquity through the Muslims into Italy and engendered the Renaissance.

The letters first flourished, the sciences then followed.

And we began receiving "the major advantage of commerce with the muses" which is sociability that inspired in people "the desire to please one another with works worthy of their mutual approbation."

IMPORTANT: he frames this as a benefit, this desire for recognition.

The body has needs which make for the foundations of political society (ruler, laws, enforcers, etc.).

The mind has its needs, for being agreeable/politeness/esteem? And these results in anesthetics for the foundations of political society.

"The Sciences, Letters, and Arts, less despotic and perhaps more powerful, spread garlands of flowers over the iron chains with which they are laden, throttle in them the sentiment of that original freedom for which they seemed born, make them love their slavery, and fashion them into what is called civilized peoples."

Arts and sciences seem to create a few things that are all about increasing dependence among people to make them easier to govern:

Increase of needs

Desire to have talents (instead of virtues)

Easy and amicable relations

The conclusion is that civilized people have all the appearances of virtues without having a single virtue.

Footnote: princes always love it when their subjects gain a taste for the arts, because it makes them more dependent and creates unnecessary needs.

Alexander forced subjects to give up fishing and eat common foods that they themselves couldn’t' produce.

Native Americans who have little needs are impossible to tame.

This politeness/civility is what differentiated Athens from Rome. But Rousseau's Europe threatens to outplay even athens.

The outside does not match the inside

People with title "philosopher" are not genuine philosophers

The principles by which people declare they follow are different from the maxims they actually follow

An athletic body is not found underneath flowery dress:

"Apparel is no less alien to virtue, which is the strength and vigor of the soul. The good man is an Athlete who delights in fighting naked: He despises al those vile ornaments which would hinder his use of his strength, and most of which were invented only to conceal some deformity."

It's not that Art corrupted human nature, humans were "at bottom, no better." (although be careful, he could mean that human nature was at bottom no better but that humans were better).

The big critique is that art and an artistic culture teaches us how to feign.

Example: first day of humanities seminar it was clear who the public school kids and private school kids were. Private school taught them the art of saying nothing in the most complex of ways.

The issue is that in an artistic culture 1. everyone is afraid of being different and following one's own genius because of the rules and regs 2. in appearance, everyone seems the same and so its impossible to know who your friends really are until its too late.

QUESTION: are these paragraphs the issue with civilization or with art and science? I suppose art teaches you how to behave like this?

Describing the consequences of this veil. So indeed human nature has gotten worse but humans have.

Important: this will appear to be enlightenment because many bad things will seemed to have gone away but they will be replaced by much more subtle offenses or the death of virtue:

No direct profanities but blasphemies that do not sound like such

No vaunting merit but disparaging others

No direct offense to others, but artful sabatoge

No national hatreds, but only because no more love for fatherland

The idea is that enlightenment limits certain vices but turns other vices into virtues.

Footnote: Montaigne says he likes doing philosophy but only for his own/its own sake. Its unbecoming to treat it like a career.

QUESTION: this means that the distant stranger would be fooled right? That he would also think modern Europeans are moral people. This is supposed to show how convincing the deception is.

Rousseau now argues that what he has observed in Europe is not just a coincidence but a necessity. This is how strong a claim he makes: "our souls have become corrupted in proportion as our Sciences and our Arts have advanced toward perfection."

He claims that their relation is as fixed as moon is to tides. This is a nod to Newton.

It is true "at all times and in all places" he now will go on to expand that history.

First example he gives is of Egypt. Which had Sesostris who conquered the world (probably got that from Herodotus), became "the mother of philosophy and the fine arts" and soon thereafter was conquered.

IMPORTANT: One (large) problem with this reading: native Egyptian rule spanned almost 3 Millenia from 3000 BC to 600 BC and art, architecture, and culture flourished for a long time. "Soon thereafter" is not right.

Second example is Greece people who vanquished Asia twice (Troy and Persia) who disintegrated from Arts and Sciences and fell to the Macedonian yoke.

This is quite accurate. Victory against the Persians were early 5th century BC. The Greek Golden Age was 5th century BC and then the domination of Macedonia was mid 4th century.

Third example is Rome. It was founded by a Shepherd (Romulus and Remus' adopted father) but degenerated with the rise of the poets: Ennius, Terence, Catullus, Ovid, and Martial. Rousseau seems to think the Roman republic reached its peak around 2nd century BC. But its thirst for conquest caught up with itself.

Petronius under Nero was named "arbiter of good taste" this is the "eve" of the fall.

Constantinople is a bastion of art and science when the western empire collapsed and all it had to show for was corruption, debauchery, betrayal. And it is through this route that enlightenment re-entered into Europe.

The last example he gives is of contemporary China (18th century). Despite having a system that directly funneled the best scholars into the administration, it fell to the Tartars.

Again, this is not a great example because the imperial exams started in the Sui dynasty (6th century) and the first Mongol conquest, the first foreign-ruled dynasty didn't happen until the 13th century with Genghis Khan.

Rousseau then contrasts these nations with the nations who were protected from vain knowledge and instead had virtue:

Early Persians

Scythians

Germans

Early Rome

The Americas (native).

Important, it was not owing to 1. stupidity OR 2. lack of exposure that these "barbarians" did not cultivate the arts and sciences. It was because they saw the people who did and what it was doing to them.

Sparta was the heart of culture in Greece. While athens had a tyrant assemble the works of poets, Sparta expelled all Art and Artists, Sciences and Scientists.

The paradox is that Athens is where you get beautiful buildings and art, its where you produce astounding works that stand as models in every "corrupt age." Athens is brilliant. But Sparta, all we have left are tails of heroic deeds. There, the people are actually virtuous.

The choice we are given is between a brilliant or virtuous state.

A few wise men did "withstand the general tide, and guard against vice in the midst of the Muses." This means that despite their education they were not corrupted.

He now introduces how Socrates the "foremost" and "most wretched" of the Athenian artists

QUESTION: Does this mean that Socrates is one of these wisemen or he has been thoroughly corrupted? I think he is supposed to be a positive exemplar "wisest of men in the Judgement of the Gods," so how could he be called "wretched?"

IMPORTANT: great intellectuals always complain about other intellectuals. That should be a give away: Nietzsche, Rousseau, Socrates/Plato.

The poets have impressive talents, they claim they are wise, but are not.

Socrates examines the artists and he says because he was ignorant of the arts, he thought they must have possessed fine secrets. But what he found was that they were no better than the Poets because both of them mistook their excellence in a particular field (TALENT) for wisdom (VIRTUE).

Socrates at least knows that he has no wisdom, that he is ignorant.

Socrates spoke in praise of ignorance. He makes an important point that Socrates did not write any books. He didn’t want to contribute to vain science. He taught men through virtuous action … namely through his death.

Cato continued Socrates' campaign against the Greek intellectuals. But Rome eventually succumbed to learning.

"Ever since the Learned have begun to appear among us, so their own Philosophers themselves said, good Men have been in eclipse. Until then the Romans had been content to practice virtue; all was lost when they began to study it."

Resurrecting two Romans from the heyday to critique Rome at its most decadent: Cineas and Fabricius.

IMPORTANT RHETORICAL PASSAGE

IMPORTANT, just like the preface, Rousseau is being somewhat disingenuous here because Fabricius fails to recognize that it is precisely the love of conquest that has destroyed Rome. That it is the conquest of the enlightened by the unenlightened that has weakened the conqueror.

Rousseau says that his time has not changed at all. Socrates/Fabricius would have given the same critique to his Europe.

Providence has made men naturally ignorant. That is why learning is so difficult: not because it is good but because it is harmful.

"The heavy veil it has drawn over all of its operations seemed sufficiently to warn us that it had not destined us for vain inquiries."

Nature preserves us from science as a mother snatches a dangerous weapon from a child.

IMPORTANT this is not on science's uselessness but the exact opposite fear that there is great danger from it. Rousseau has in mind the social dangers but we might as well add the technological dangers from science.

The first part of it is history we now move on to examine science and art in themselves.

Rousseau says that his conclusion: probity is the daughter of ignorance and science and virtue are incompatible.

Rousseau begins with a genealogical attack

An ancient Egyptian tradition states that a God wishing to disturb man's tranquility was the inventor of the sciences.

Footnote: Rousseau's claim is that the Greeks were also suspicious of Prometheus and they were the ones who nailed them to the mountain.

Example: emperor Tiberius.

Rousseau suggests that the origin of human knowledge is vice not virtue and thus we should be suspicious of their advantages:

Astronomy from superstition

Eloquence of ambition, hatred, flattery, lying

Geometry of greed

Physics of a vain curiosity

Ethics of pride

QUESTION: help me understand geometry, physics, ethics?

The flaws in their origins closely mirror the flaw in the objects. The critique is that without these "objects" we wouldn't have use for these arts. Which means the arts didn't "cause" these objects but are reliant on them (and maybe the suspicion is that they encourage them for their self-interest).

Arts and luxury

Jurisprudence and injustice

History and tyrants, wars, and conspirator (it would be boring if everyone just did their duties).

QUESTION: the metaphor he uses is we are destine to die tied to the edge fo the well into which truth has withdrawn. The implication being we have a perverse need to get at the truth (tied) but we won't be able to (withdrawn)?

QUESTION: what exactly is the critique here of these as the objects? This is different from effect and origin. Origin is made to make you suspicious. Effects are the most important. What do these objects tell you about art?

Rousseau continues describing the difficulty of the question for truth:

To get to the truth we arrive at many falsehoods that are dangerous.

Falsehoods have an infinite number of combinations whereas the truth only has one.

So few people desire the truth "sincerely" as opposed for vanity/reputation/etc.

How will we recognize truth when we arrive at it? And what is our criterion for it?

Even if we have arrived at it, who among us will know how to use it?

We now move from the origin and the objects of science to their effects. The first effect is idleness and uselessness.

Rousseau thinks every useless citizen is actively harmful. Perhaps this isn't just because he himself is useless but he spread that uselessness he gives a model of being useless.

IMPORTANT we have a very different answer to this question than Rousseau now, but Rousseau asks a rhetorical question of what has science really done for us.

"Answer me then, illustrious Philosophers, you to whom we owe it to know in what ratios bodies attract one another in a vacuum; the proportions between areas swept in equal times by the revolutions of the planets; which curves have conjugate points, which have inflection points, and which cusps; how man sees everything in God; how there is correspondence without communication between soul and body, as there would be between two clocks; what stars may be inhabited; what insects reproduce in an uncommon way. Answer me, I say, you from whom we have received so much sublime knowledge; fi you had never taught us any of these things, would we have been any the less numerous for it, any the less well governed, the less formidable, the less flourishing or the more perverse?"

He says, if even the greatest outcome of our greatest minds are so useless, what about all those obscure writers and intellectuals who do nothing.

When you talk about the power law of outcomes, surely art and science is one of the greatest.

It's even worse than that! They don’t remain idle instead they go and undermine public mores.

What motivates them is not a hatred of virtue or dogmas but public opinion.

The even worse evil is Luxury, it is not caused by science (as idleness is) but the arts and letters.

Where there are arts and sciences there must be luxury. Where there is luxury there almost always are arts and sciences.

Luxury causes people think not in terms of virtue/vice but in terms of commerce and money.

Gives examples of poorer nations defeating richer nations.

IMPORTANT: the interesting thing that this teaches about us today, is never before has commerce and intellect been so tied together.

States must choose to be brilliant (ostentatious) and short-lived or virtuous and long-lasting.

The concern for commerce makes minds "debased" by host of futile cares and splintered.

Artists primarily care about recognition.

IMPORTANT observation that scholars care a lot more about recognition than merchants, people in industry.

Therefore, if an artists were to be born in a tasteless time. He would sacrafice his masterpiece to create popular work

IMPORTANT that rousseau does not hold out the standard of an artist who does art "for its own sake" you always seek someone's recognition. The correct recognition to seek is of many centuries past.

This is why he thinks taste his declined:

The young are in charge of setting the tone.

Women are setting taste and women are not being properly educated. IMPORTANT its not the ascendency of women itself that is the problem but that they don’t have the right taste. This is why women's education is so important for Rousseau:

"I am far from thinking that this ascendancy of women is in itself an evil. It is a gift bestowed upon them by nature for the happiness of Mankind: better directed, it might produce as much good as it nowadays does hart. We are not sufficiently sensible to the benefits that would accrue to society if the half of Mankind which governs the other were given a better education. Men will always be what it pleases women that they be: so that if you want them to become great and virtuous, reach women what greatness of soul and virtue is."

He claims that Voltaire is guilty of this, pandering to the public, to fashions.

If someone in such a society with corrupted taste were to hold steadfast of soul, he would die in poverty and obscurity.

QUESTION: how does Rousseau explain his own rise?

Morals were best in a simple age when men lived in huts. When people's homes started looking like magnificent temples, mores became corrupted.

Gives two examples of how study of sciences soften men's courage rather than strengthen it.

Italian princes amused themselves to become more ingenious and learned than to practice warfare.

Important to know that Rousseau is not pro-war, but he is using this as a way to convince his readers that one wouldn't be able to defend oneself.

When Goths attacked Greece they didn't burn the libraries because they wanted them to keep distracting their enemies.

Roman military virtue declined in proportion as they started cultivating the arts and sciences. Rise of the Medicis destroyed whatever martial values Italy managed to recover.

Modern soldiers may showcase bravery for the day but cannot bear long periods of extreme labors.

It's not that they themselves have studied too much art and science but the culture they live in do not encourage these martial values. Example being them seeing that their officers do not even have the strength to go on horseback.

Success in battles (which enlightened states can do) is different for success in war (difficult for enlightened states). What you need is not only courage but judgement.

Question: why do enlightened states' officers lack this?

Answer: next paragraph.

What is also being threatened are the moral qualities. Education is disastrous teaching them superfluous knowledge while not teaching them any necessary virtue.

Footnote: Montaigne says that despite the Spartans being surrounded by culture they only needed role models of bravery.

And he gives an example of how when the education of Persian rulers went from role models and doing to teaching about ethics, everything went down the gutter.

All of our paintings are of aberrations from ancient Mythology so that children can learn bad deeds even before they can read.

The issue is that a society has translated the appreciation of virtue to the appreciation of talents. People don’t ask whether something is useful for political society but whether it is well-written / beautiful / etc.

IMPORTANT even the wise man is not insensitive to recognition (even if he will not chase fashions). Even he needs emulation, role models to seek in order to develop his virtue which instead languishes.

We have developed all these professions of learnedness but we no longer have citizens.

But the remedy is right next to the injury. Monarchs built academies to 1. develop human knowledge 2. protect the morals of a society.

These societies by upholding morality will inspire men of letters, who hope to join them, to behave morally.

We should be very cautious of Rousseau's praise here.

Question: what is the charitable way to read this, perhaps rhetoric? (the uncharitable way would be ass kissing)

Philosophers are charlatans hawking on public square. The advice he gives is esotericism.

Philosophers ought teach their ideas to only friends and children.

IMPORTANT perhaps this was the biggest issue with the imperial examinations:

"So many organizations established for the benefit of the learned are al the more apt to make the objects of the sciences appear impressive and to direct men's minds to their cultivation."

Printing made things much worse

He points out the sectarian wars that it has created ("reign of the gospel").

People like Hobbes and Spinoza will last forever.

Oddly enough Rousseau sees a future where descendants who read these works will come to his side and ask to be returned to ignorance, innocence, and poverty.

Footnote: Rousseau forsees a time when wise rulers will destroy printing presses. He gives examples of why the burning of the library of alexandria is a good thing. Because we need nothing other than the Holy texts.

The worst are the popularizers and the anthologizers, the big issue is spreading knowledge to those unworthy.

Rousseau argues that the great geniuses such as Descartes and Newton not only needed no teachers but would have been limited by them. Instead, they needed to go on a path of their own.

QUESTION: this is the sudden twist: "if one wants nothing to be beyond their genius, nothing may be beyond their hopes." And now he advocates for his ultimate solution which is the joining of politics and enlightenment. That these intellectuals should be directly placed into office.

QUESTION: Why isn't the honor of being a preceptor of humanity not enough? Why is being advisor to some king better?

QUESTION: how does this not get entangled with this "So many organizations established for the benefit of the learned are al the more apt to make the objects of the sciences appear impressive and to direct men's minds to their cultivation."

"Let Kings therefore not disdain admitting into their councils the people most capable of counseling them well."

Rousseau now calls himself a part of the talentless "vulgar men." He says that he is not destined for so much glory and that he should be content in obscurity.

QUESTION: I thought for the entire work this would be impossible "What good is it to seek our happiness in someone else's opinion if we can find it within ourselves?"

Final paragraph tying few things together:

It's time to return to oneself (learn the science of man) that is genuine philosophy.

We should stop envying the men of letters who made themselves immortal through artistry.

We should be Sparta to their Athens.

Discussion about this post

No posts