* These are notes on the Introduction and Abstract Right

Hegel justifies the institution of private property on the basis of freedom. What’s interesting about this, all too familiar, move is the original and unintuitive breadth the concept of freedom takes in Hegel. Far from being merely an instrumental means valuable in so far as it can bring about other more substantive ends, freedom becomes a substantial and, in fact, the primary human end. It is within the immanent demands of freedom alone that Hegel finds reasons to justify private property. Therefore, we should expect our investigation to reveal something original and informative about the value of private property beyond what they have to offer our more concrete ends such as safety, comfort, and pleasure. The aim of this essay is to make clear how exactly freedom justifies private property. I will proceed in two steps. First, I will outline the shape and demands of freedom. Second, I will critically reconstruct how private property alone can satisfy these demands.

The Shape of Freedom

The landscape of freedom cannot be outlined without involving the will, for the will is to freedom what weight is to physical bodies (§4). The former is the constitutive characteristic of the latter. If freedom is broadly understood as self-determination, then the will is nothing but that substance which seeks to self-determine. All human beings have wills. It is what separates us from inanimate objects and instinctually driven animals.

To better understand the logic of the will and, thus, the demands of freedom, it is fruitful to understand it under the light of the more familiar faculty of thinking. In fact, thinking is contained in and nothing but the theoretical side of the more practical will. “The will is a particular way of thinking - thinking translating itself into existence [Dasein], thinking as the drive to give itself existence” (§4). For Hegel, thinking has three distinct moments. First, thought removes any determinacies from its object. When I think about the color black it is not any instance of a black object I conceive, but rather black in the abstract. Second, through thought I, the thinker, “can penetrate an object” (§4). The idea here must be that thinking is able to break apart concepts, construct new ones, and shape them according to my ends. And thirdly, because of this, I make whatever object my thinking has grasped “mine”. In like manner, the will has three corresponding moments.

The Three Moments of Will

The first moment of the will, that of universality, is the negative and abstracted state of the will. It is active when consciousness is directed at itself, when the only thing in focus is the abstract “I”. As far as the first moment is concerned, this is simultaneously a movement in which the will directs its attention back on itself and pushes away from any determinacy it was embedded in. Hegel provides us with two examples of this first moment. The French Revolution, so Hegel interprets, descended into a religious fervor that became just about negating and tearing down ideals instead of establishing any positive formations. The same negative capacity obtains full dominion over the Hindu mystic’s mind in meditative states of transcendence (§6). Lest we think that the first moment is reserved for as extreme conditions as these, I add a third, more common, example. Anytime we pull away from one of our urges – when we refrain ourselves from smoking a cigarette for example – Hegel would describe the precise psychological mechanism as a disidentification from and externalization of the urge to smoke and a retreat back into our will.

The first moment of will is free, or, self-determining in two senses. First, the form of the will is such that it gains a self-conception according to whatever object it has as its content. If I eat an apple, I take upon a self-conception of an apple-eater. Under the same logic, if the content of the will is itself then its self-conception is defined by nothing other than itself. Second, because the will always has the capacity to break free of any determinacy, it is always capable of being free from any external influence. A consequence of this position is that Hegel maintains, later on, that even a will which is coerced is, in some sense, responsible because it failed to withdraw itself from the source of coercion. “Only he who wills to be coerced can be coerced into anything” (§91).

But, in this moment, the will is also unfree for two reasons. First, the will is still determined in a particular way despite it not having any determinations. The will’s continued reflection on itself ad infinitum may seem to be infinity, but it is only an extremely limited form of it. It is an infinity that is bounded by all finite determinations instead of one which encompasses all finitudes. By refusing to be limited by any particular determination, the first moment becomes one sided, empty, and, paradoxically, limited by the entire set of determinations. It is thus defined by something distinctly other. Second, and closely related to the first, the will is not free because the will is not anything yet. There is no content nor existence to it; what is reflected to itself is vacuous. “A will which … wills only the abstract universal, wills nothing and is therefore not a will at all” (§6). The will in the first moment is free for-itself because it is only to the will looking in on itself that the will appears free. But this is a thin self-conception of freedom. Because you do not determine anything, you can’t conceive of yourself as a full self-determining agent.

The second moment of the will, that of particularity, is the state where the will resides in some determinacy. The will “emerges from undifferentiated indeterminacy to become differentiated, to posit something determinate as its content and object” (§6). It should be clarified that, in so far as my will’s actuality is concerned, I have a similar relationship to my desires and urges as I do external objects – I can embed my will in or abstract my will away from the former as I do the latter. Therefore, the second moment sees my will imbued in both subjective and objective determinations. My will first chooses between the host of subjective urges to give it character and then pursues the external objects in the objective world that would satisfy these urges. When I choose to satisfy my hunger and then pick out the type of ice cream to eat, my will is imbued in both the subjective ends and objective means. Consequently, both the ice cream and the hunger determine my will, however so subtly, by changing my self-conception. But we should not think that the constitutive capacity of the second moment is choice. In the case of, say, citizenship, my will can reside in a determinacy even if I did not actively choose. The second moment is just the state of the will that resides in some determinacy.

The second moment can be seen as a dialectical progression of the first, simply because the former resolves the ways which the latter was not free. This second moment is free because it adheres more closely to the ideal of self-determination. No longer is the will bounded by all of finitude nor is it empty and vacuous. The will is now actually determined in a real and existing object. Yet, it is only a dialectical progression and not an absolute one, because the second moment is not free in a sense that the first was. The form of consciousness makes it such that the will no longer conceives of itself in relation to itself which is freedom, but rather in relation to a finite, alien object, be it a subjective urge or objective externality. The will’s self-conception is determined by an alien other. The will is no longer free for-itself – it has lost the self-conception of freedom – but merely in-itself – it is the embodiment of freedom in the object.

To render the abstract more immediate, think of a loveless and abusive relationship. I clearly see that my partner is determining the content of my reality but not in a way aligned with the rest of my life: they may hit me, take away my savings, and verbally abuse me. And I can’t help but conceive of myself as “partner-of-my-partner”. That is to say, deep within my conception of the self lies an element that the same self finds terribly alien and unappealing. Because my life is furnished with content not determined by my self, I do not gain the consciousness of being a self-determining agent.

The third moment of the will, that of individuality, is the state where the will resides in determinacies that is not alien to it. It is an absolute progression from both the first and second moments because it is the unity of the first two moments. Like the second moment, it is free in-itself because the will resides in determinacies. But it is a greater degree of freedom in-itself because these determinacies are not alien to me. They are, in some sense, “mine” in a way that was not true in the moment of particularity. What could this mean? I will not attempt a systematic and exhaustive account of what it means for something to be “mine” but only provide suggestions to illuminate the concept. One way something can be “mine” is if it exists in harmony with the other determinant ends that I have embedded my will into. It is not unthinkable that a sibling whom I considered “mine” in childhood when we shared hobbies begins to develop an alien and other character when our interests diverge or even conflict. But we need not interpret “harmony” so thinly. I may lose in an athletic competition that upset most of the ends I held in life. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the entire competition must appear alien to me. Upon recognizing the fairness of the rules and the clear superiority of the victors, I may nonetheless consider the competition legitimate and, in some deep sense, “mine”. Another way is if I choose to determine my will in accordance to a set of ethical principles recognized as good by me. I may, reflecting on the importance of companionship, move to a foreign country for a romantic partner. Even though I am in a, literally, alien situation, I can still observe the surroundings as reflecting my principles and, thus, “mine”. There are two broad sets of strategies to unalienate the determinations of the will. I can, practically, transform these determinations. Upon seeing a hole torn into my roof by a tornado, I can go repair my roof. I can also, speculatively, change my interpretation of these determinations and look for ways that existing circumstances are already aligned with me. The same tornado-ridden home owner can, perhaps, learn to see the hole as a work of God that serves to constantly remind him of the frailty of life. As it should already be obvious, there are different degrees of freedom even within the third moment. The former homeowner may be right to question whether the latter’s reconciliation is deficient. But what is constant throughout these examples, and what I have hoped to have illuminated in Hegel’s concept of freedom, is the assumption of an immense desire to be at home in the world. This is a desire to belong and, just like when we are at home, see our needs accounted for or reflected in the world’s workings even if they are not all addressed. To the extent we don’t feel alienated but reconciled in our determinations we are free in-ourselves through the content of our will.

But “the will is determined by no means only in the sense of content, but also in the sense of form” (§8). Like the first moment, the third moment is free for-itself because it has a self-conception of freedom. This should not be overlooked. Both the fact of being determined by myself and my conception as a self-determined agent are two distinct species of reward that come from this conception of freedom. As is the case with freedom in-itself, the moment of individuality has a more fleshed out freedom for-itself than the moment of particularity because it now sees this freedom reflected in actual determinations. The idea must be this: in so far as I am reconciled to my determinations in the ways I’ve articulated and consider them to be “mine”, I also gain a conception of myself through the form of my will as a self-determining agent simply because nothing which determines me is alien. The will is free in-and-for-itself.

For an example, now consider a harmonious romantic relationship. My partner may make demands of me that don’t align with my immediate ends. But they are reasonable enough for me to see how they are in alignment with the sustainability of this loving relationship which I, without a doubt, consider “mine”. Because all the determinations – my partner, their demands, etc. – which affect me are reconciled to me and do not take on an alien character, I gain a self-conception of a being that is determined solely by myself.

The numerous examples I provided in romance may lead to the misconception that the three moments are meant to be interpreted as developmental stages. Indeed, it is often the case that we, first, do not express ourselves, second, express ourselves incongruently and then, third, find a coherent expression of who we are. But I suggest we interpret the first two moments as mere logical stages for the reason that I cannot conceive of any real instance where a human will is just for-itself without any determinacy or just in-itself without any self-conception of being a free agent. That is to say, we shouldn’t expect to find a solely universal or particular will in the real world. Every instance of will in reality is free in-and-for-itself although, of course, each may vary in deficiency of freedom in-itself or for-itself.

The Double Question

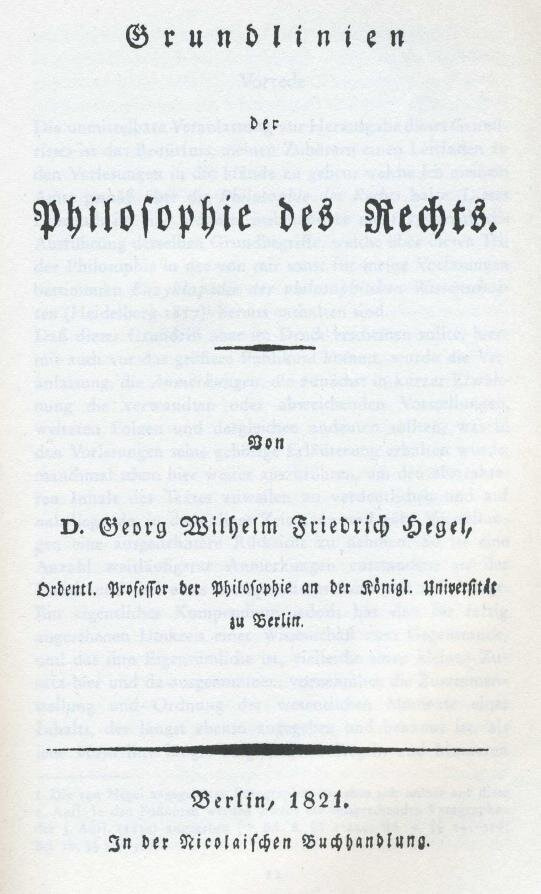

Before we continue to examine how private property is justified upon this conception of freedom I have sketched out, we must ask a question that will add complexity to our investigation: where does this conception of freedom and the forcefulness of its demands come from? Another way to put the question is: how solid is the grounding that grounds property? For, at the end of my deduction, one can agree that private property is necessary based on this conception of freedom but still fail to see why this particular conception of freedom is meaningful or should encompass the entirety of our ethical concerns. I suspect, admittedly without an understanding of the entirety of Hegel’s system but merely deducing from the fact that new demands of freedom are introduced continuously throughout the Philosophy of Right, that Hegel’s conception of freedom is not deduced completely a priori. This is a marked difference from, say, Locke and Kant who justified property on purely a priori grounds: natural law and the Universal Principle of Reason respectively. Hegel’s conception of freedom is indeed informed by some a priori analysis of the agential structure but it is also informed by empirical observation. That is to say, both the what – the specific demands of freedom – and the why – why this conception of freedom is ethically meaningful – is revealed partially in the empirical investigations of the Philosophy of Right. Having just finished the Introduction, the demands from Hegel’s will are much less forceful than those from Locke’s natural laws or Kant’s Universal Principle of Reason. It gains force and legitimacy only by revealing itself and its demands to the reader as foundational to the human condition throughout the rest of the book. According to the reading I am proposing, the Philosophy of Right is as much an account of justifying institutions based on an account of freedom as it is about justifying the ethical meaningfulness of a conception of freedom by showing how it manifests in our institutions. Therefore, the single question that motivated our investigation – “How does Hegel justify private property on a conception of freedom?” – expands into a double question – “And how does Hegel justify his conception of freedom through a discussion of private property?”

Property and Contract

The entire section on Abstract Right is grounded on the most barebones and basic conception of freedom in the three subdivisions: the freedom of personhood. Persons are those who exercise an arbitrary will, a will that chooses to engage with and disengage from certain determinations. It is the fact of choice rather than the principles of choice that are of concern in personhood. In other words, Abstract Right is the set of conditions that guarantee the person’s capacity to choose can be exercised. What is at stake here is whether a person is able to express themselves at all rather than what form that expression takes: “The person must give himself an external sphere of freedom in order to have being as Idea” (§41). As far as property is concerned, it is irrelevant whether one chooses to be the next Beethoven or a drug-dealing criminal. We should not confuse this disinterest in the principles of choice with only the second moment of particularity. It is made clear that one is only a person in so far as they have realized, at least to some extent, all three moments of the will. In personality “there is knowledge of the self as an object \Gegenstand\, but as an object raised by thought to simple infinity and hence purely identical with itself. In so far as they have not yet arrived at this pure thought and knowledge of themselves, individuals and peoples do not yet have a personality” (§35).

So how does Hegel justify private property – a normative relationship legitimizing a thing as “mine” – upon the conception of personhood? The answer is deceptively simple. Persons have an arbitrary will that demand to be actualized in the ways I have discussed. Things do not but can be vessels for the will of persons. To completely prohibit private property is to prevent the will from claiming any thing as its own. Wills will not be able to realize freedom in-itself nor freedom in-and-for-itself. Because the actuality of the will is, as Hegel puts it, “sacred”, a social order must permit a sufficient sphere of things where people can inject their will into and claim as their own as long as it is not inhabited already by another will.

This system-side argument must seem empty and weak. After all, one can question why the actuality of the will is sacred. Ceteris paribus the two species of good we’ve unveiled in Hegel’s conception of freedom – to be unalienated from the world and to hold a self-conception as a free agent – are undeniably valuable. But why are they sacred above all else? We should not expect to understand the importance of private property as an institution and, indeed, to see the sacred value of freedom in Hegel’s formal arguments. Instead, the reading I am proposing suggests we can only hope to find such reasons by wrestling with the empirical reality of property ownership as Hegel describes it. Hegel observes that what is constitutive of private property is possession, use and, alienation (§53). To this I add, while withholding an explanation of my reasons for doing so until a later section, contract. These four relationships to a thing are not the preconditions to property nor the license that property provides but what owning property is. That is to say, to the extent a thing is in my possession, used by me, has the potential to be alienated, and is verified in contract, it is my private property and my will is embedded into it. It is through an empirical investigation into each of these constitutive relationships and the goods that result from their actuality as well as the evils resulting from their prohibition that we can understand both the importance of private property as well as freedom.

Possession is the external form of property (§64). One can possess physical property through physical-seizure, form-giving, or signature. Physical-seizure, as the name suggests, is any external hold you may have over the object. This can take the form of literally picking a fruit from a tree, building a fence around a piece of land, or grabbing something with your remote-controlled robotic arm. As it should be apparent, the forms of physical-seizure greatly varies and what separates the rightful from the illegitimate cannot be fully deduced from the concept of property. This will be true for all the constitutive relationships discussed: philosophy can only provide a general outline of what owning property is, leaving the details in positive law for actors in history to flesh out based on their contingent circumstance.

Form-giving is to mold the object in some way or another, say, when you design your living room. “To give form to something is the mode of taking possession most in keeping with the Idea, inasmuch as it combines the subjective and the objective” (§56). That is to say, it’s obvious how this species of possession is fundamental to the moments of will we have discussed. To give form to something is to both fashion an object according to my will and express my will through an object.

Lastly, a signature – when you plant a flag on a building or when you write your name on a box, for example – is the most abstract and fundamental type of possession. In fact, both physical-seizure and form-giving are types of signatures. Signatures are a way of labeling an object externally as “mine”. Their necessity must come from the demands of the will: only through them can we construct a homely environment and gain a full self-conception as a free will by seeing myself reflected in objects I consider “mine”.

So, what negative formative consequences result from prohibiting possession? Let us imagine a specific communitarian outpost where workers tend to a garden owned by all. Workers would still be able to seize and give form to things (in fact, I can’t imagine a situation where they can be universally prohibited) but they aren’t able to give signs to their labor, at least not in the way Hegel instructs. Workers would look to their fruits as the outcome of collective labor; the sign is “ours” instead of “mine”. What is so disastrous about this? The answer must be that by only seeing things as owned by the collective and not recognizing anything owned by myself, I gain a false self-conception. I do not recognize myself as an agent with a free will, but only agential in so far as I can act through the larger collective. It is not that I may starve or the garden will be poorly managed but that I won’t be able to consider the communal garden a home and thus fail to recognize my freedom. Indeed, this is the charge Hegel levels at Plato’s communitarian property ideals. It “misjudges the nature of the freedom of spirit and right and does not comprehend it in its determinate moments” (§46).

If possession is the external form of property, then use is identical to the internal presence of the will in a thing (§64). Possession is the positive relationship to a thing as “mine”. Use is the negative relationship to a thing: I see it only as a function of my needs with no positive qualities of its own. “The thing is reduced to a means of satisfying my need” (§60). To own property is to be able to use it fully, to have your will embodied in it fully. The dictates of right are that not only must I be able to use things from time to time, but only by allowing me to fully hollow out objects of any other considerations than those of my will am I able to see the entirety of myself and my needs reflected in it. The negative formative consequences of prohibiting ownership may be easier to see than possession. Consider a slave that does not have full use of anything, not even their own body. Such a slave may even be permitted to do something enjoyable like to knit. But since both the tools and fruits of knitting are owned by the master, the slave isn’t able to reduce the activity of knitting solely to the satisfaction of their desire to knit. They might worry whether they have used too much of the master’s yarn, or whether they will be banned from knitting all together at a moment’s notice. The activity and, therefore, also their desire for knitting both begin taking on an alien character. They do not conceive of themselves as self-determined but heavily other-determined beings.

Alienation is the ability to disown property. It is dictated by right because it corresponds to the first moment of the will: the ability to disengage from any determination. A society can fail to protect the right to alienate in two ways. First, it can fail to provide sufficient channels to alienate our previous determinations. A real example of this is the suggestion to introduce a “right to be forgotten” which protected the individual’s ability to remove a piece of personal content from the internet. The idea here also underlies the right of alienation: if we don’t allow people ways to distance from certain identities they have chosen in the past, we do not provide the conditions for them to self-determine in the future. They will always be stuck with something alien. Second, a society can permit too much to be alienated. “The right to such inalienable things is imprescriptible, for the act whereby I take possession of my personality and substantial essence and make myself a responsible being with moral and religious values and capable of holding rights removes these determinations from that very externality which alone made them capable of becoming the possessions of someone else” (§66). The idea here is this, I can alienate something in so far as I can externalize it, stop using it, and draw my will out of it. There are a certain set of things – personality, body, morality, religion – that I can indeed abstract away from but I cannot do so without it losing its function. I can indeed, perhaps in a state of deep meditation, abstract away from my personality and body. But in so far that I have a personality, that I use my body, that I engage in moral thinking, that I am religious, it must be my will alone that is fully embedded inside these determinations. Thus, it is contradictory to be able to alienate them. This is not the case for my car, for example, which I can completely externalize while preserving its function for transportation that can be successfully used by another without involvement of my will.

I also include the contract as a constitutive relationship of property for the reason that without contracts, property is, in a certain sense, deficient. The basic form of the contract is to exchange one’s property for that of another. We should not underestimate what is at stake here, the prohibition of the contract will, at the same time, remove the very basis for the market economy. While we may make contracts for specific determinate ends, the necessity of the contract is mandated by the demands of freedom (§71). In fact, the discussion around the contract further furnishes our conception of freedom. What is required in the freedom of personhood is not only that I own property, and gain a self-conception of being property-owning, but that I see others recognize me in this way as well. “Existence … as determinate being, is essentially being for another” (§71). This reciprocal recognition required by freedom is what contracts affirm: “Contract presupposes that the contracting parties recognize each other as persons and owners of property” (§71). Imagine a society that permits the first three relations of property but not that of contract-making. An artist in such a society would be able to create, own, and even abandon artworks but not trade them for money. The concern here must be that the artist does not gain a full-conception of themselves as an artist. They may see their will reflected in the work, but without the implicit recognition that others see them in this way too – as would be gained in an art sale – their self-conception is deficient.

Conclusion

There are already fault lines beginning to emerge in this line of argumentation already. Hegel’s choice to ground his state on freedom, especially the formative demands of freedom, seems to be trapped between two horns of a dilemma. If freedom and its realization is shown to be just one amongst many of human goods, then his theory is on shaky grounds. After all, I may be able to properly conceive of myself as a self-determining agent by joining a self-sufficient but poor and starving group of nomads. Yet, after consideration, I still prefer the life of a well-fed Roman slave that is, on occasion, able to enjoy certain comforts not available to the more realized nomad. Yet, if freedom is shown to underlie all human goods, I struggle to imagine how the definition of freedom will not have been bloated and abstracted to such the extent that it is no longer a useful concept. The fear here is that freedom becomes empty and vacuous, uninformative in making practical decisions.

But even if we were to concede that the demands of freedom are indeed sacred, one can still reasonably question whether it necessitates private property in the ways Hegel has described. In ethical life, we will learn that the family does possess communal property without harming the freedom of its members. Why can’t the same not be true for our communitarian garden laborer? Furthermore, can’t our artist gain recognition from others without selling his artwork? It is intelligible how contract promotes this mutual recognition as property-owners, but why is it the only way necessitated by right? Lastly, a danger of grounding private property on its formative consequences for our self-conception is that it appears to permit the state to prohibit what we would normally consider to be protected under private property. After all, if private property is necessary only because through it we develop a self-conception that would otherwise be impossible, isn’t it enough just to give me property rights to my body and nothing else?

So, where do we stand with regard to the double question? Has Hegel shown private property to be necessitated by freedom, and that this particular conception of freedom to be sacred? In a sense, it is still too early in the book to provide a definite answer, especially for the latter question. Both property and freedom will receive much more substantial treatment in morality and ethical life. At this point, these potential problems I have highlighted should just be reasons to be even more intrigued for Hegel’s resolution in the rest of the book.